Godzilla is a 2014 film written by Max Borenstein and directed by Gareth Edwards. It stars Aaron Taylor-Johnson as bomb disposal expert Ford Brody, whose journey to Japan to retrieve his father (Bryan Cranston) turns into a life-or-death struggle against gargantuan ancient radioactive creatures called MUTOs (Massive Unidentified Terrestrial Organisms). Ford volunteers for increasingly dangerous missions in an effort to reach San Francisco, where the monsters have convened, in a desperate bid to save his wife and child before the devastation reaches them.

Meanwhile, Ken Watanabe plays Dr. Ishiro Serizawa, the lead researcher for Monarch, a multinational coalition formed in 1954 in the wake of the discovery of Godzilla. Monarch’s main goal is to contain and study the MUTOs, but Dr. Serizawa has a more sympathetic approach to Godzilla, believing him to be a force of nature superior to mankind. Dr. Serizawa argues repeatedly for Godzilla’s autonomy and believes that Godzilla will save them all.

Contextualizing Godzilla

It is interesting to note that Dr. Serizawa does not argue on behalf of the other two MUTOs featured in the film. This is likely because Japan’s relationship with Godzilla has changed significantly over the last 60 years. In the original 1954 film Gojira, Godzilla is a loose allegory for the devastation of Japan following World War II and the subsequent nuclear test bombings in the Pacific. Thus, Gojira is a creature to be feared and defeated. However, in the last few decades, Godzilla has evolved into an antihero; a mascot for the people of Japan.

For instance, in the 2004 film Godzilla: Final Wars, Godzilla is reawakened to save the earth from a host of invading monsters. Godzilla is still a creature to be feared, but with this fear comes respect. This change is reflected in Dr. Serizawa’s attitude. All of the MUTOs are indicative of nature’s extreme power, but only Godzilla has ever used that power to save the people.

The Japanese versions of Godzilla following the original in 1954 are seen as niche films in the United States. So it makes sense that Dr. Serizawa’s feelings of awe and wonder are not shared by his American counterparts. When Dr. Serizawa’s assistant refers to Godzilla as “the top of the primordial ecosystem- a god, for all intents and purposes,” Ford corrects her, calling him “a monster.” As an American, Ford is not equipped to understand Godzilla’s relationship to the earth and to the Japanese people. He has never seen what Godzilla can do.

This is further driven home when Admiral Stenz orders a nuclear attack on the MUTOs. Dr. Serizawa responds by showing the admiral a broken watch. Dr. Serizawa claims that the watch was his father’s, and it stopped at 8:15 AM on August 6th, 1945, the day the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. The point here is not to shame Admiral Stenz, but to contextualize the destruction Stenz is proposing. Dr. Serizawa is not just an expert because he has studied Godzilla, but because he is Japanese. The legacy of World War II has shaped his worldview. Stenz has never seen an entire city reduced to rubble in the span of a few seconds. He has never seen an act of God.

Godzilla Ex Machina

Deus Ex Machina (or “God from the Machine”) is a storytelling device in which an external force or character intervenes on behalf of the heroes to resolve the final conflict. The concept has its roots in ancient Greek theater, when a literal machine would “fly” the gods onto the stage. Ancient Greece’s concept of godhood was far different from our own. Ancient Greek gods were beings of immense power, but they were not moral figures. For the most part, the gods were treated as neutral parties. Often they were observers, occasionally interlopers, but rarely saviors. These were figures that inspired awe, not love.

As audiences grew more savvy, Deus Ex Machina became less favorable, partly because this device rarely affords a satisfying conclusion for its characters, and partly because it fails to appeal to the skepticism of modern audiences. However, that is not to say that Deus Ex Machina has disappeared altogether.

The Battle at the Black Gate battle rages, and the Nazgul fly through the air on their dread Fell Beasts. Death seems certain. A moment of stillness. Gandalf spies a moth as a heavenly voice punctuates the harsh clangs of metal on metal. Pippin looks up, his eyes wide with wonder, and he exclaims, “Eagles! The Eagles are coming!”

-J.R.R. Tolkein, The Return of the King

Many of our favorite films use this device, often to great effect. Raiders of the Lost Ark features a violent retributive divine intervention, while Life of Brian opts for a humorous alien joyride. War of the Worlds chooses a more thematic Deus Ex Machina, in the form of bacteria. It subverts the audience’s expectations by choosing the smallest “god” imaginable. Jurassic Park (in a very entertaining disregard for object permanence) saves its heroes from certain doom by plopping a T-Rex right into the middle of the fray.

Godzilla uses Deus Ex Machina. More to the point, Godzilla is about what it means to experience Deus Ex Machina. The ancient Greeks were overjoyed by the appearance of the gods in their plays. But would they be overjoyed by the appearance of the gods in their everyday lives? To see them? Touch them? To be so minuscule, so insignificant, so helpless by comparison?

How would your senses even comprehend something so large, so powerful, so ancient, so other? What can you do when you come face to face with the unfathomable?

Perspective Maketh The Monster

What does Godzilla look like? The easy answer is that he looks like a giant lizard. But what does Godzilla look like to a human being on the ground? That’s a far more interesting question.

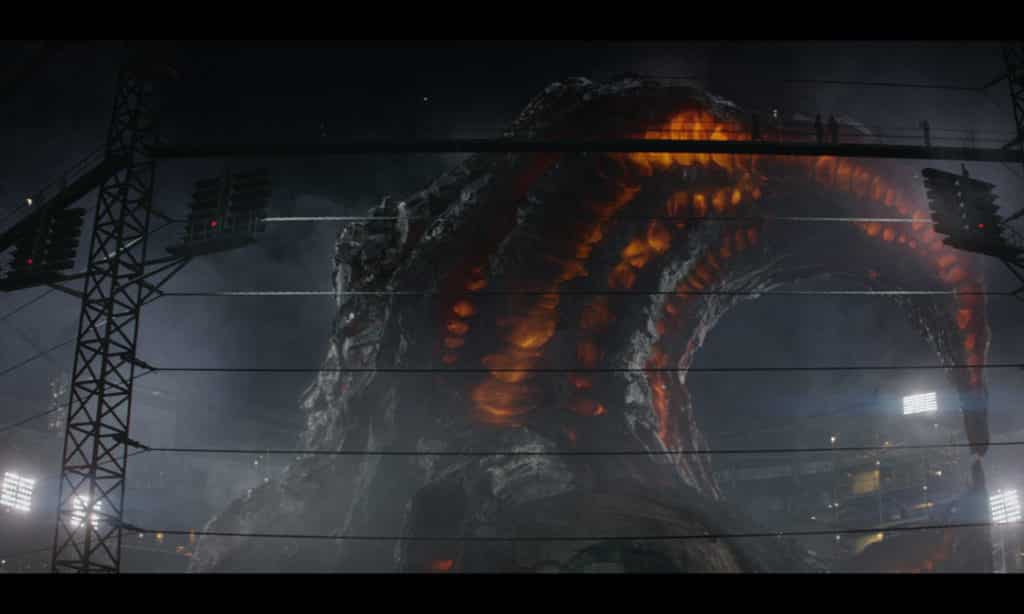

One of Gareth Edwards’ strongest assets as a director is his understanding of scale. When it comes to a creature of gargantuan size, it is more important to frame it than to show it in all of its glory. A giant monster cannot exist in a vacuum. Together with his incredible cinematographer Seamus McGarvey, Edwards deftly integrates his monsters into each scene. For instance, the first sequence with the MUTO perfectly utilizes digital effects and camerawork to lend credibility to the monster.

Joe Brody’s position on the scaffolding gives much-needed wide perspective while Ford Brody’s position on the ground gives us a more chaotic close up perspective. These two perspectives, married with regular reminders of their relative positions, give the scene a sense of reality.

Combining the use of wide, medium, and close up shots throughout helps us to contextualize the action.

Bite-Sized Terror

In order to feel true terror at its appearance, we must take it in parts. So we start with a close up of a minuscule part of the monster, a tendril. We then move to an extreme wide shot of Joe Brody to get a sense of the scale and overall action. The area is huge, the people are minuscule. The monster is larger than everything else in sight.

We follow Ford and other engineers on the ground with handheld shots as we continue to take in visually digestible pieces of the MUTO: a leg, then a head, then two legs, etc. Eventually, we get an extreme wide shot of Ford. He is facing away from the camera, tiny in the foreground. The monster erupts from the depths. The same shot is now a close up of the monster. But the camera doesn’t move. It stays on Ford as the thing continues to rise, to grow, to engulf the entire view of the camera lens.

For a moment, we pan to the creature’s head, then we follow its feet as it wreaks destruction on the human beings below him. The MUTO isn’t just another monster. He is truly awe-inspiring.

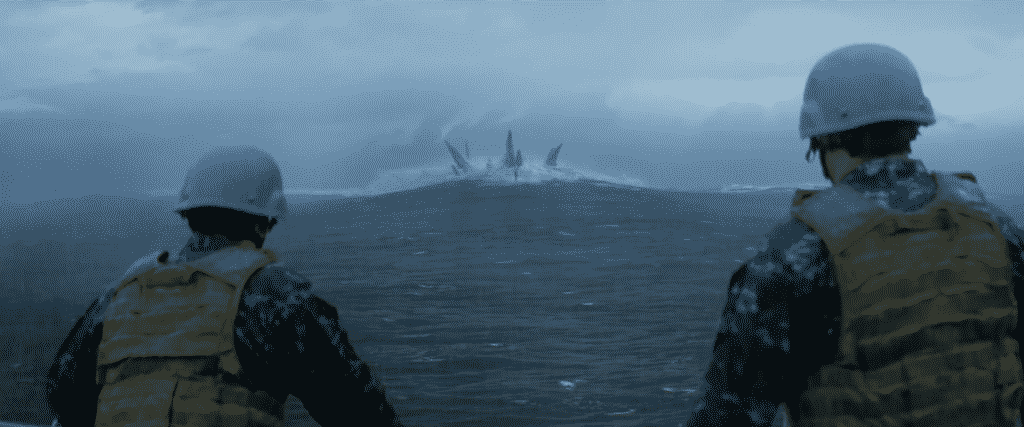

The effective visual style of this scene holds true for the rest of the film. Crowds of people running away from the giant monsters are not shot with a drone or a crane or a helicopter. These are handheld shots, on the ground, where the people are. The monsters are often filmed through windows, as if the footage was caught by a spectator. However, unlike found-footage films like Cloverfield, Godzilla is not limited to a single point of view. Just as nature photographers capture their subjects using many different techniques, so too do Edwards and McGarvey. Their creatures just happen to be digitally rendered. It seems like Edwards and McGarvey were looking to capture the footage of the monsters in as many ways as possible, from every conceivable angle, but always with one eye on the human perspective.

HALO

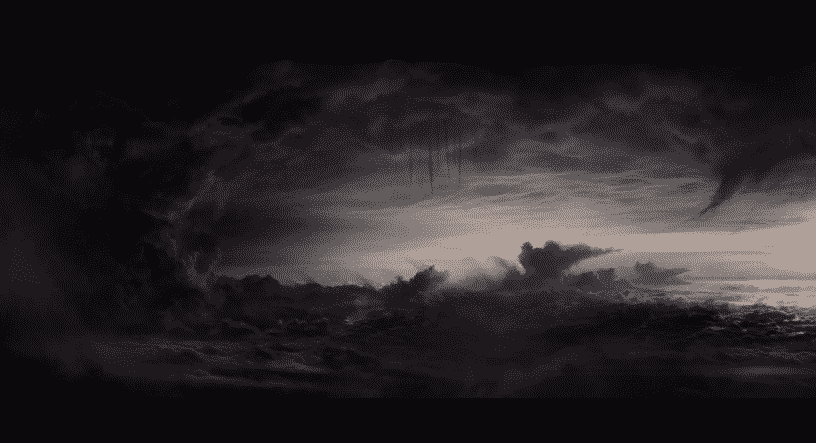

The HALO scene is the culmination of Deus Ex Machina themes and the visual style of Edwards and McGarvey. Ford Brody volunteers for a mission to retrieve a live nuclear bomb from the MUTO. Since the city is in ruins and the MUTOs fire EMPs, the team must parachute to the site using a High-Altitude, Low Opening (HALO) jump.

The plane door opens to reveal a perfect golden sun, and as the paratroopers make their jumps, Gyorgy Ligeti’s Requiem begins to play. (For Kubrick fans, this is the same piece used in the climax of 2001: A Space Odyssey.) Ligeti’s music is haunting, even frightening. Our heroes plummet through seemingly endless space as the clouds below and around them crackle with thunder and lightning. Then the skies open, and for a few moments, we see a wide shot of the expansive sky. The clouds form wispy stalagmites and stalactites, the beautiful sun from before just a whisper of pink and purple in the distance. Ligeti’s music invokes timelessness, the void, the unknowable infinity beyond our limited horizons. We hear the sound of warm oblivion caressing an immense empty expanse of sky, and we think: This sight is surely reserved for the gods.

Then we are thrust into a first-person perspective, the majesty of the heavens reduced to the murky view behind Ford’s goggles. He falls below the clouds, looks around, tries to make sense of what he is seeing. We hear his breath, fast and shallow. He sees a head, he sees scales, a flapping wing, a silent roar, an epic battle too large for him to comprehend.

The Deus Ex Machina is a terrible thing to behold.

But Was It Good?

Godzilla is far from perfect. No matter how amazing the bells and whistles are, a good movie must first have good bones. The screenplay is unfocused and for the most part, uninspired. The acting is very hot and cold, with Bryan Cranston giving an incredible performance that sets expectations perhaps a bit too high for the rest of the cast. Important emotional scenes are often glossed over or completely omitted.

More than one death/ reunion is skipped, and this makes it hard to identify with many of the characters. Ford Brody has too much in the way of tragic backstory to be an effective blank slate protagonist (like Neo from the Matrix), and he doesn’t have enough agency and charisma to be a heroic figure either. This often leaves us wondering, “Why does the camera keep following this guy?”

Sights and Sounds

That being said, I think Godzilla is truly an astonishing feat of film-making from a technical perspective, and technical achievement should be lauded just as much as writing and acting. As mentioned previously, the cinematography is wonderful; far better than any other giant monster movie I’ve seen. Weta’s digital effects are always beautifully designed and rendered, and this film is no exception.

Alexandre Desplat’s score is incredible, nimbly jumping from John Williams-esque ominous minimalist techniques, to the atonal screeching strings of traditional horror films, to complex poly-rhythms reminiscent of Stravinky’s “Rite of Spring.” In particular, any sequence in which Godzilla himself appears was a joy to listen to.

Erik Aadahl’s sound design is truly astonishing, breathing life into these giant creatures. Godzilla’s roar is satisfyingly deep, piercing, and rich. The real wonder though, is the MUTO sound design. They sound like creaking stones and exploding volcanoes. Insects in a frenzy. Machinery whirring. Every noise that comes from the MUTOs is alien, off-putting, and yet so familiar. Closing my eyes and listening to these strange sounds, I imagine a mix of organic and synthetic, an ancient wrongness, a cyborg Balrog.

Final Thoughts

I didn’t expect to like Godzilla. Giant monster movies aren’t generally my thing. The movie has faults (a lot of them, in fact), but it’s hard to fault its sincerity. Godzilla was clearly a labor of love, and that love can be seen on every frame of this film.

Recent Comments